In his book “moonwalking with Einstein” Joshua Foer, a journalist, sets out to become the world memory champion and on that journey, he explains how our brains store memories. In the process, he stumbles onto one of the most important ways that our brains function, association, and metaphor.

We can move from a thought about Barry White to the colour white to the milky way and back to a cow in a field. It’s a very long conceptual journey but only a very short trip from association to association, from one neurological path to an adjacent neurological path. It seems that metaphor and association are critical and essential to how we think.

It’s a complex network of understanding one thing associated with and in the context of another. In fact, this is not only the thinking process but also begins to explain why we are hard-wired for creative thinking.

Metaphor, from the Latin “to carry over” or to transfer, allows us to understand one concept in the context of another. By conjoining two different concepts or idea we can sometimes find a completely new, emergent, idea that changes our understanding. Metaphor allows us to broaden our understanding whilst broadening our culture and knowledge.

Metaphor allows us to layer meaning and add fresh insights. Metaphor embraces ambiguity and isn’t subject to fact or truth and is one of the key tools of our imaginations. Abstract concepts are often very difficult to understand if we don’t use some method, as a metaphor, to link the concept to something we already know. This enhances our perceptual understanding by borrowing attributes that shed light on the thought.

When we think of a how a mind works, we often apply the metaphor of the computer, which may actually be incorrect, but nevertheless allows us to create a mental representation of short-term memory, RAM, and longer-term memory, the hard drive. This then allows us to be able to conceptualize further meaning as to how the mind works.

We use metaphor extensively and intuitively in language. The actual letters of a word and the word itself is meaningless unless we can attach a meaning to them via a mental representation which anchors the idea or concept. So, we learn to use complex and diverse representations to symbolize the meaning by using another representation to hook the word onto. Dog, for instance, has multi-layered meanings and those meanings will change in a given context. If we go even further, we layer up the meanings into say, “dog of war” “raining cats and dogs”. Language is one long-running metaphor of complex meanings that we share with other people.

Our brains are hard-wired for pattern and pattern is the repetition or connection of one event with another. When we see (or fabricate) a pattern in our minds we begin the process of making meaning by association and connection. These connections that have become stories allow us to be able to predict what will happen next and thus reduce the uncertainty of not knowing. Beau Lotto, in his book “Deviate” explains that one of the driving forces of human existence and creative thinking is our desire to escape uncertainty by making meaning in order to be able to better predict our future.

These driving forces change our behavior and increase our collective knowledge, which then further drives our behavior, which in turn changes the way we think. Thinking processes are not linear they are circular, or spiral, (now there’s a metaphor) and increase the collective consciousness, which allows further, deeper concepts to form.

Consider the phrase “Juliet is the Sun”. This is obviously false and a little nonsensical but the metaphor adds a deeper meaning to Juliet which enhances our mental representation of her. She has the qualities of radiance, brilliance, she makes the day when she gets up in the morning. The metaphor adds a level of truth even though it is literally false.

The visual aspect of the metaphor should not be played down. However, it is the full sensual aspects of metaphor that really sheds light on our thinking processes. If we think of Proust’s “A la recherche du temps perdue” it is the Madeleine that evokes his childhood memory. As he dips the crumbs of his cake in the tea on his teaspoon he finds;

“An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin”

The association of the sensation brought a sense-based memory to the front of his mind.

This seems to confirm that our memories are associative and metaphorical and that the brain stores information with a complex system of remembered sensations and associations and not as linear film stories. It’s not the volume of information the brain contains, but, by association, the ease with which it can retrieve information. A book index will provide a single address, a page number, for important subjects. Yet each subject in the brain has hundreds, if not thousands of addresses. It’s associative and metaphorical not linear. You don’t need to know where a particular memory is stored in order to find it. And we can skip from memory to memory and idea to idea very rapidly.

This is why memory techniques such as the memory palace are so effective. By associating an event with something else we can “hook” a thought onto a long-term memory store from the short-term memory which can only hold a small amount of information.

We do this by “chunking” together (or hooking or pegging) information so that the brain can quickly retrieve the thought.

For instance, if I ask you to remember the following numbers 12741091101, it’s unlikely that you will remember them in 5 minutes. The average person is capable of holding about 7 items in their short-term memory for a minute or so. However, if I were to chunk them into small clusters, as we do with phone numbers, say, 127 410 911 01, you might have a better chance of recalling them. Particularly if you repeat them rhythmically for a few minutes.

If you want to able to recall them easily though I would put them in this form; 12/07/41 (pearl Harbour attack) 09/11/01 (twin towers attack). I’m pretty sure that you would be able to recall those numbers.

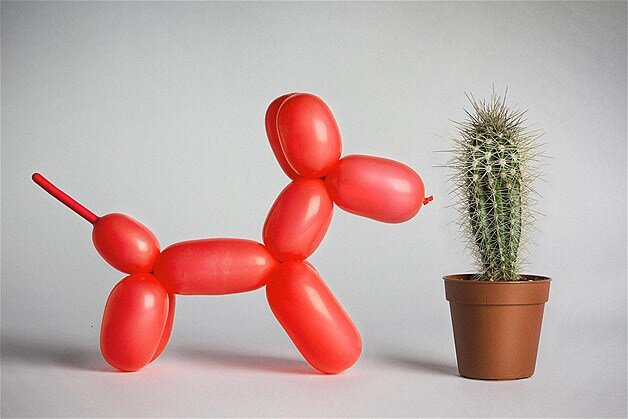

When things are emotionally and sensually linked to existing “experiences” they are shifted from short-term to long-term memory. It also turns out that the more crazy and vivid your associations the better you will be able to recall them.

Likewise, metaphors add a depth of understanding and meaning and enrich the thinking process. Thinking creatively is based on how the mind works, by sensation, perception, association, and metaphor. Metaphorical thinking is a very powerful tool in problem-solving, by enabling a view of the problem from a completely different perspective.

Previously we all understood the structure of the atom as being the same as our solar system. When Kekule discovered the structure of Benzine he did so with the visualization (metaphor) of a snake devouring its own tail. Einstein mentally chased beams of light. For special relativity, he employed moving trains and flashes of lightning to explain his most penetrating insights. We can form mental representations of “string theory”.

Mental representations, including associations and metaphors, are at the very heart of perception and our ability to understand and give meaning to the universe we live in. They layer our perceptions with greater depth that sheds light on new meanings that advance, not only what we think but also how we think.