One of the great debates particularly when my kids were young, was whether you could or should use a carrot or a stick to encourage them to “do better”. I was always in the carrot camp, but my wife was always in the perfectionist (stick) camp. She felt that it was better to “say it as it is”, although there was always a discussion about what standard that had to meet and what “perfection” might be.

The problem, as I have always seen it, is that perfection is unachievable and negative criticism often entrenches kids in their feeling that they can’t do it and should just give up before they even start.

As chance (if it was chance!) would have it, both kids have grown into whole human adults with happy, meaningful and purposeful lives. But I have always been left wondering as to what the best method might be for influencing and motivating behavior.

So, i looked into some recent research into what motivates behavioral change carried out by neuroscientist Tali Sharot of UCL, which sheds a bit more light on the debate (and, of course, confirms my position).

Without any doubt, we all have behaviors we’d like to change, the difficulty is knowing what actually best motivates people to change their behavior.

Most people use a negative threat to scare someone into changing their behavior. Like smoking kills or no dessert until you finish your homework, and we even do this to ourselves too. No chocolate if you haven’t been to the gym…

The assumption seems reasonable, give a strong negative imperative in order to change behavior. But science has found that threats have a very limited impact on changing behavior. Fear generally produces either freezing or fleeing and we tend to post-rationalize our behavior to better fit the story we want to hear; “My father smoked till he was 80 and nothing happened to him!”,

Negative warnings often make us feel even more resilient.

Sharot gives the example of people who invest in the stock market. When there is a bull market and prices are rising people tend to log into their account more frequently to give themselves a piece of positive feedback, a reward. Positive information makes you feel good. Yet when it’s a bear market and prices are falling, people often bury our heads in the ground and avoid painful feedback, at least until it’s too late (Karlsson, Loewenstein and Seppi 2009). We, understandably, tend to prefer good news (and we want to indulge in it) than bad news (we want to ignore or avoid it). People only log in when the situation becomes critical or frantic.

According to Daniel Kahneman’s prospect theory, people tend to fear loss more than they love gain, and will often be motivated to avoid loss and pain. Positive information makes you feel good so you go looking for it.

In another study involving People were asked what they felt the likelihood of something bad happening to them in the long-term future. You might say 50%, however, the results change depending on how the information is framed.

If you were to go to your doctor and ask what are the odds of surviving cancer, given your medical records and your family history one doctor may say, “you have a 40% chance of survival” and you might think that sounds OK. But if another doctor were to frame the same information as; “you have a 60% chance of death” you will probably come away from that appointment feeling depressed. We prefer to hear positive information.

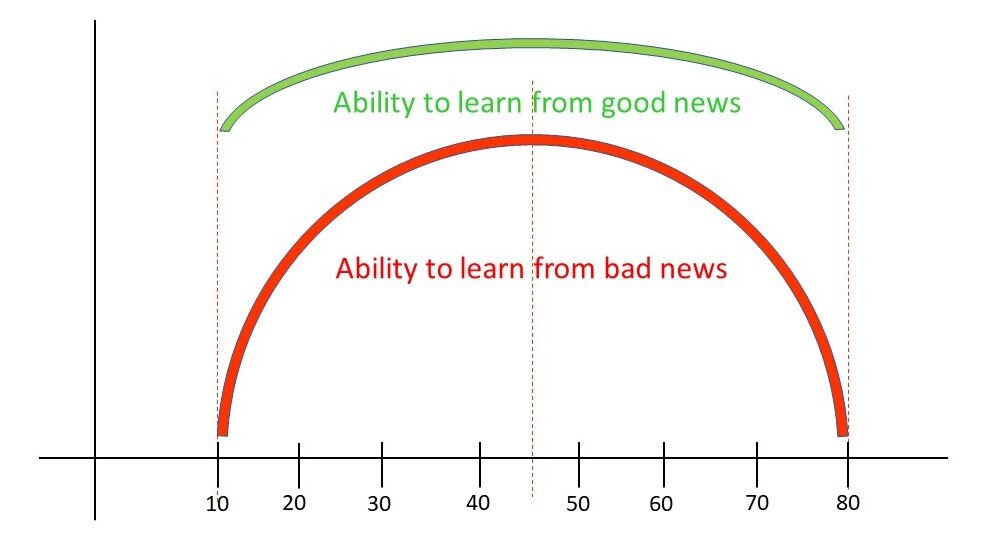

Our ability to learn from bad news changes with age, whilst our ability to learn from good news only changes a little with age. The most vulnerable people, teenagers and those in old age are the most likely not to learn from warnings.

We all take in the information we want to hear rather than information we don’t want to hear, so we end up with a distorted view of ourselves, and rather than work with the positive image we try to place in front of them an image of what we consider the “truth”. The difficulty is that the “truth” is not how the brain works, it wants to distort the image until we have an image, or story that our brain wants to hear.

Sharot gives a very powerful example of working with how your brain works (these methods are not dissimilar to the way advertisers think. See Alchemy by Rory Sutherland). She and her team conducted an experiment in a hospital with regard to hand-washing.

In the hospital, they put in a camera to see how often medical staff washed their hands before and after entering a patients’ room. They let the medical staff know that there was a camera installed and yet, only 1 in 10 washed their hands before and after.

Then they introduced an electronic screen which told the medical staff how ell they were doing so that every time someone washed their hands before and after the numbers went up on the screen. The results were astonishing, from 1 in 10 to 9 in 10. The experiment was replicated in other wards and they found the same results.

They found that the reasons the screen worked so well were because it set up 3 fundamental motivators.

1. Social incentive.

The leader board encouraged them to see what others were doing and created some social pressure for conformity.

2. Instant rewards.

Because they could see, straight away, the effect they were having and that they could influence that result gave them a quick reward. These were not long-term rewards, but small instant rewards. Short rewards have been shown to give us a psychological uplift.

3. Progress monitoring.

Medical staff could see the trend of their actions and this also gave them a sense of control.

Having a sense of control and influence is an important factor in influencing how people will behave. Our brains want to control the environment and be rewarded for that control.

The imperative for social cohesion is also a very strong human (and some animals) motivation and has its roots in evolutionary advantage.

As far as I can see and as the evidence of research shows;

Fear induces inaction.

The thrill of gain induces action.

As a species, we have a tendency to seek quick rewards, social cohesion, and progress. That doesn’t mean we should avoid reporting risks though.

So, stick or carrot? It’s carrots (almost) all the way…