If the sun rises on the eastern horizon every morning, are we right to expect it to do so tomorrow?

Well, yes and no!

Let me explain because things aren’t quite as they seem.

According to the philosopher, David Hume our expectation is irrational, and, as I’ve mentioned before, irrationality is what we do best and goes to the heart of how we think we think.

You’d probably be right to say “the sun has risen every morning for millions of years, so there’s no reason to assume it won’t do the same again tomorrow”. Well, yes probably, but we have no more reason to be certain that the sun will rise than we have to say it won’t, or that a giant bunny will rise instead of it in the east. In fact, it’s only our belief that the sun will rise and for that matter, the same applies to many other things too including all our scientific theories.

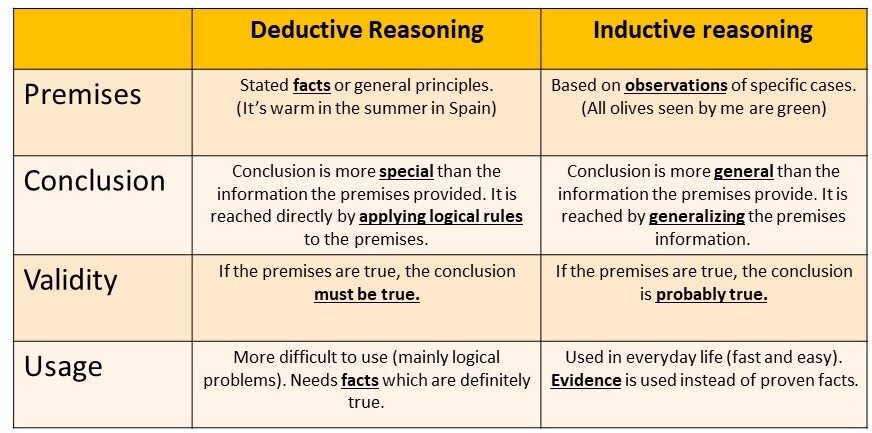

This needs a little explanation. Let me start by briefly explaining the difference between Deductive and Inductive thinking as these are the key tools we use to understand the sensations coming in from our senses and our interpretation of the world.

An argument is made up of one or more claims or premises and a conclusion arranged in such a way that the premises are supposed to support the conclusion.

Deductive arguments.

Deductive arguments will normally take the form:

P. Richard follows a vegan diet. If A is B

P. Vegans don’t eat meat, and if B is C

C. Therefore Richard doesn’t eat meat. Therefore A = C (assuming A & B are true)

Two things are needed for a valid argument. The premises must be true and the argument must be valid. i.e. the premises must logically entail the conclusion, otherwise, you would have a logical contradiction.

Inductive arguments.

Suppose you only see green olives. You have never seen anything other than green olives. You would have a pretty good idea that olives are al green. Your reasoning may look like this:

P. Rose 1 is Red

P. Rose 2 is Red

P. Rose 3 is Red

P. Rose 1000 is Red

C. Therefore, all Roses are Red. (?!)

Here the premises are supposed to support, but not logically entail, their conclusions. It is, or so it would seem, more likely that all Roses are red. The premises support the conclusion, so we believe that our conclusion is justified, even though it doesn’t offer any logical guarantee that if the premises are true then the conclusion will be true.

Inductive reasoning is how we arrive at most of our beliefs and assumptions about things, even if we haven’t necessarily observed them in every possible (that would be impossible) case. However, inductive reason allows us to formulate stories and beliefs from our observations and predict what will happen in the future.

This sort of assumptive thinking is essential (dare I say critical) for us to be able to move in this world. It is a basic survival skill. If we weren’t able to predict if a tiger might attack, by the time we’d evaluated all the possibilities, we’d end up as dinner.

We assume, for instance, that the ground below us will support our weight and so we can progress in the likelihood that it will continue to support our weight. But it doesn’t logically follow, deductively, that the next piece of floor will support my weigh, even though every piece of ground (except perhaps a frozen lake) has always done so.

We are hard-wired for these kinds of assumptions, based on inductive thinking, so that we can predict the future of an event. When we see events following events in the same pattern, we begin to assume and believe that they will continue in that way into the future and have done so in the past. That’s why we make stories, create assumptions (although there are other reasons such as mental energy conservation too), and why we form beliefs. Prediction is a survival and energy-saving mechanism that our brains employ.

So, I can’t justify, by logical deduction, that the ground will not collapse under my feet. I need to use inductive reasoning, based on experience.

Science is heavily dependent on inductive logic. The only evidence we have is based on our observations and leads to our predictions of how phenomena will behave in the future. Science is often an observation of events that form patterns that suggest their behavior in the future. So, we rely on inductive reasoning to justify our beliefs and science.

Hume says that “induction rests on a wholly unjustified and unjustifiable assumption.

So, back to the sun rising.

Assumptions

We make an assumption based on our observation that the sun will rise again in the morning because it has always, as far as we can tell, risen in the past and that nature is uniform and predictable. i.e. it follows a pattern that we can apply so that we can predict its behavior from the distant past and into the future. We “assume” (albeit that the “evidence” may be overwhelming).

If you didn’t believe (assume) that nature was uniform you couldn’t conclude that the sun would rise tomorrow. (we couldn’t exist without these assumptions).

The philosopher Stephen Law gives an example of an ant on a bedspread. The ant can see a paisley patterned area and assumes that the rest of the bedspread is also paisley patterned. But it may not be so. It may be a patchwork bedspread with many different patterns. However, the ant believes that his universe is paisley-patterned because that is all he can see.

This is also a concept called Umwelt. We see the world as we are, not necessarily as it is (or might be).

We cannot justify our assumption that nature is uniform. We have to use inductive reasoning which in itself is unjustified. We have to appeal to experience. We only have our five senses to provide information. We are dependent on our senses for our brains to make perceptions (and assumptions and beliefs).

We can only infer, from what we see around here and at the present time, and that, in itself is an inductive argument! So, our justifications are circular.

A friend of mine mentioned an astrologer recently who was a source of very reliable information. Let’s call her Mystic Maud. My friend trusts her because she says she’s trustworthy. Obviously, that is no justification at all, you would need a reason to trust her before you could trust her claim that she is trustworthy. Otherwise, your justification would be unacceptably circular.

So it is with nature. To justify it we have to pre-suppose that induction is reliable.

So, Hume’s argument that all inductive reasoning relies on an assumption that nature is uniform, seems justified and we can only infer from what we have observed and experienced. i.e. locally. So, we cannot justify assumptions. Our trust in induction is unjustified.

But, Induction Works, doesn’t it!

Ah, but it works for us you say! That’s true (no pun intended). Inductive reasoning has allowed us to build nuclear power stations, put a man on the moon, discover the human genome, and develop supercomputers. So, it seems that induction and assumptions are, after all, a reliable way to produce true beliefs. You might say that induction has worked up to now and therefore will continue to work in the future. We’re back to the same circular argument.

If we didn’t believe in our inductive thinking other people would think we were insane. Induction supports insane ideas and concepts about the future as much as ideas that (seem to be) sane and rational.

During the second world war a religion worshipping airplanes was founded on the island of Vanuatu, a remote island in the South Pacific of Australia. Food was delivered to the islanders by airplanes. The islanders had no idea where the food came from and believed that it came from the Messiah and if the constructed a runway with lights, a tower and an airplane, they could induce the airplanes to return and deliver food. (You can read the story here).

Richard Feynman mentions them in his 1974 lecture;

"They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they're missing something essential because the planes don't land."

Following very logical, even scientific, reasoning (inductive reasoning) doesn’t necessarily lead to a correct conclusion. (unless the Vanuatu Islanders know something we don’t)

All it means, according to Hume, is that we cannot be certain of what will happen tomorrow. Things may continue in the same way. The sun will probably rise tomorrow (or perhaps a giant bunny will come bounding over the horizon). Rationally we shouldn’t believe, but we just can’t help ourselves, we can’t stop ourselves believing.

We have no choice but to believe that regularity and uniformity will continue because we are hard-wired to make patterns that we develop into stories that become our beliefs.

For instance, George believes in astrology because he finds that the predictions are quite often right.

There is no good causal justification for this belief. It's not rational. But it is something George is stuck with. His belief points to an uncontested truth that doesn’t need or want any justification or cause.

Like the Vanuatu islanders and George, we can’t help but create meaningful stories that give satisfactory explanations for how the world works. Without assumptions based on heuristics, we couldn’t progress. We couldn’t build our stories and we couldn’t build our cultures.

A bit less Sherlock Holmes and a bit more Vanuatu.