After Umberto Eco.

I listened to the Trump – Biden presidential debate earlier this week and whilst they bickered and spoke over each other, the phrase - “inventing the enemy” popped into my mind. Like Brexit, the current presidential election race in the US is dividing the people into polar divisions: you’re in one camp or another; if you’re not for me, you’re against me.

Spy Vs Spy - MAD Magazine - Michael Riedel

Some years ago, Umberto Eco wrote an article, originally given as a lecture at the University of Bologna in 2008, about how we invent enemies, even where none may really exist. The premise of the article is obvious in the title, but what is not so obvious is our primal need to identify with our in-group or out-group, so that we may gather together our allies and pitch ourselves against another group, our enemy.

Eco begins with a story in a New York taxi. The driver of the taxi, originally from Pakistan, began a conversation with Eco which goes something like this.

Driver: “Where are you from?”

Eco: “From Italy”.

Driver: “What’s the population there, what language do you speak?”

Eco: “57 million and we speak Italian”

Driver: “So few, and you don’t speak English.

Driver: “Who are your enemies? Who do you fight against?”

Eco: “We’re not at war with anyone!

Eco: “We don’t have any enemies!”

Eco: “We fought our last war more than 50 years ago!”

This didn’t satisfy the driver. “How can a country have no enemies?” That set Eco to thinking; It’s not that Italians don’t have any enemies, we just don’t have any external enemies, rather, Italians are unable to agree on who their enemies are because they are at war with each other – Pisa against Lucca, North against South, fascists against partisans, mafia against the state. However, Eco regrets the fact that Italy doesn’t have any real enemies.

World War 1 Posters. Released 1917 - Harry Ryle Hopps.

In the UK we have Brexit, with Remainers and Leavers, those for Europe and those against. In the US you have Trump supporters and the “others”, variously described as “crooked”, “corrupt”, “liberalist”, “leftist”, and also “communist.”

Having an enemy provides us with an obstacle with which to measure our own values. When we unite and seek to overcome that obstacle, it binds us into a common cause and allows us to define our own identities. We identify with groups who are not only “for” something, but also “against” something else.

Trump is following a long line of world leaders who have sought to align our allegiances with theirs by inventing an enemy. He is a master at it and a master of the sound bite. Whether it’s the far left, the communists, the far right, or the Democrats in the USA; or the so-called “looney-left” or “champagne socialists” or Brexiteers in the UK, they are the objects of our derision… and our unification. Enemies unite us in a common cause.

Generally, we will assign lower status, physically and mentally, to our enemies. They are ugly, they have physical features that may be different from ours, even to the point of saying they are deformed, sub-human. They might smell or their personal hygiene is poor. They have immoral rituals, perform strange rites, and have different customs. We will assign derogatory names for them. They kill babies and drink their blood, they eat garlic and their breath smells, they have hooked noses, they are hunch-backed, they are short, they worship false Gods, they speak with a funny accent, they wear the wrong clothes, they are poor, they are the “arrogant” rich, they are corrupt and evil. This type of language, and so much more, is used to confirm our collective unity, values, superiority, and status as a group - in effect our “tribe”.

Throughout history, we have depicted anyone not in our chosen group as “other” than us, starting with children in the playgrounds, to those who run our countries. We assign our fears and suspicions to them. We differentiate between insider groups and outsider groups.

One of the reasons we do this is due in part to the way our brains work. To save mental energy, we “chunk” things together into bite-sized groupings that become our assumptions and stereotypes. Think of stereotypes as mental caricatures, exaggerated shortcuts that make it easy for us to find and recall huge amounts of associated information. We assign to a whole ethnic culture the characteristics of a few of its marginalized members. Thus, a negative stereotype evolves into a sacrificial example. It serves the purpose of simplicity, economy, and emotional resonance. It is vividly memorable and serves to unite us in our fear of outsiders.

In 1954 a social psychologist, Muzafer Sherif, conducted what is now known as “The Robbers Cave Experiment”. Groups of boys were invited to a summer camp and separated into two groups. The experimenters wanted to see how the different groups behaved towards each other within their groups and outside of their groups. The boys were carefully vetted and all came from normal well-adjusted backgrounds. They spent the early part of their stay at the camp within their allotted group only, unaware that another group existed.

Lord of the Flies - 1963 film

As a result, each separate group developed its own norms and group hierarchies. They chose their own names, in this case, the Eagles and the Rattlers. The groups made their own flags and each established its own code of behavior. This bonded the group as a unit, consolidating the identity of the group.

When the groups were made aware that there was another group at the camp, they began referring to the other troop in negative and pejorative terms. They became competitive against the other group. The researchers then moved the study forward by putting them in a competitive tournament against each other, with games such as baseball and tug-of-war, where prizes were awarded to the victors.

Once the Eagles and Rattlers (shades of Montague and Capulet) began competing, the relationships escalated and the groups quickly became aggressive and tense towards each other. They began trading insults. Competition between the two groups soon spiraled into conflict. They burnt each other’s flag and raided each other’s cabins.

In surveys distributed to each group, the researchers found that group hostilities were aimed at the other group. Each group was asked to rate their own group and the other group on positive and negative traits. The campers rated their own group more positively than the rival group. During this time, the researchers also noticed a change within the groups as well: the groups became more cohesive internally.

In order to reduce conflict, the researchers tried to bring the campers together for fun activities, such as having a meal or watching a movie together. This didn’t work, meals together quickly devolved into food fights.

The researchers did manage to find a way to reduce this conflict, by getting the boys from both teams to work together on a project that had a shared goal. In one exercise they cut off the water supply to both huts. The groups had to work together as a larger team to restore the water supply and thereby found a common goal that benefitted both groups.

The infamous Brexit poster

The Brexit image on the left shows Nigel Farage inventing the enemy on the side of a mobile poster. The image is remarkably similar to Nazi propaganda that identified, in pejorative language, immigrant as the enemy.

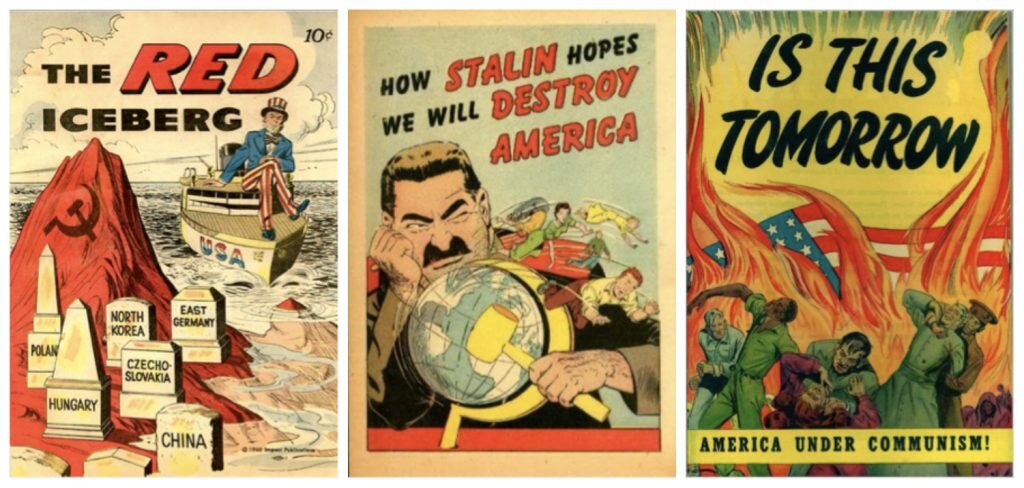

Inventing the enemy is something we do naturally in order to establish our own allegiances, our identity, and status within our peer group. This natural disposition has been exploited by politicians and warlords for centuries (think McCarthyism in the 1950s, the Crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries, WWI and WWII propaganda) and indeed also forms an important element in sports allegiances and political support.

When I was at school, all the pupils were divided into “houses” (as in Harry Potter, Gryffindor, Slytherin, Ravenclaw, and Hufflepuff, etc.) These were specifically designed to create both loyalties and competitive rivalries. In the US movies Fraternities and Sororities work in much the same way.

When we hear our leaders speaking about “the China Virus” or “drain the swamp” or “Crooked Hillary,” it is one the one hand divisive and on the other, unifying.

The Brexit campaign in the UK portrayed immigrants (on the side of a bus) as a queue, miles long, waiting to enter the UK, and take our jobs (as a result of European legislation). This polarised the population into two distinct camps; Stay or Leave and thus unified the Remainers and likewise the Leavers. Clearly, the identification of an “enemy” served the purpose of clearly unifying one side against the other.

Perhaps in times of war, this is an acceptable strategy. The inevitability of war is inexorably linked to identifying an enemy. People need to be galvanized into action and that is best done by identifying, and vilifying, your enemy. Then we are unified in a common cause; you’re either with us or against us. War (but not only war) enables a community and a society to understand itself as a “nation”.

If we want to understand other people and live in harmony, we have to destroy the stereotypes without taking away or ignoring their “otherness”.

“We can recognize ourselves only in the presence of an Other, and on this, the rules of coexistence and submission are based. But it is more likely that we find this Other intolerable because to some degree he is not us. In this way, by reducing him to an enemy, we create our hell on earth.”

Umberto Eco – Bologna University May 15, 2008.

We naturally invent enemies in order to unify our allies in a common cause directed at an “outsider” who doesn’t belong to our in-group. We form or adopt opinions and then rally forces into an agreement with our point of view. Without common shared causes and goals, we lose our identities within our communities. These communities may overlap and, as in the case of Eco’s vision of Italy, may sub-divide internally. However, the creation of both enemies and allies (strong and weak) allow us to unify groups and consolidate shared aims.

Cold War Posters - 1947 - 1960